San Diego Surf (1968) is one of the later films from the period in which Andy Warhol made sexploitation films. These include: My Hustler (1965), I, a Man (1967-68), Bike Boy (1967-68), The Loves of Ondine (1967-68), The Nude Restaurant (1968) Imitation of Christ (1967-69), Lonesome Cowboys (1967-68) and Blue Movie (1968). In terms of chronology, San Diego Surf falls between Lonesome Cowboys and Blue Movie, Warhol’s final work as a director. Both Lonesome Cowboys and Blue Movie would run into censorship problems, but San Diego Surf, which was filmed shortly before Warhol was shot and seriously wounded by Valerie Solanas, was never released. Now, forty-four years later, the film has been restored and finally makes its debut on October 16 at the Museum of Modern Art, where it will be introduced by the legendary Taylor Mead, who starred in it. The film will have an extended run at the museum from January 23–28, 2013.

Although the sexploitation films were initially dismissed by many critics and scholars, a revisionist perspective on this body of work has emerged over the years. In his book, Andy Warhol and the Can that Sold the World, Gary Indiana, for instance, writes: “Whatever else could be said of them, [the sexploitation films, or what he deems ‘the crypto-narrative talkies’] are among the most audaciously, emphatically spellbinding displays of polymorphic sexuality and verbal frankness in film history, in part because of the camera’s, or the director’s, disregard for continuity or narrative construction, the inclusion of unintelligible stretches of sound track, the pockets of total silence, the use of stuttering zooms, and, confuting their deliberately amateur qualities, a mixture of innovative and classical framing, the inclusion of synechdotal figures and evocative objects at frame edges, and the improvisatory brilliance of actors provided with the sketchiest story premises to work within (when they remember to).”

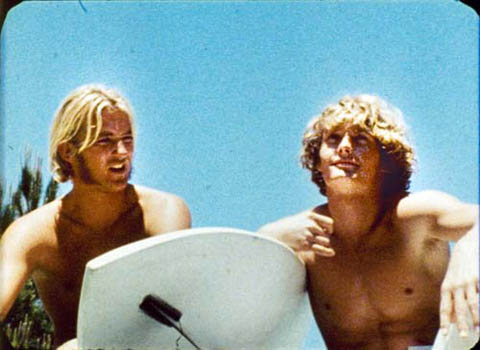

The plot of San Diego Surf will certainly strike viewers as “sketchy.” Viva is married to Taylor Mead, a rich property owner who is supposedly a golf and tennis champion, but he can’t manage to climb the social ladder of La Jolla because he’s not a surfer. On the verge of getting divorced from Viva, Taylor indicates that he plans to marry Nawana Davis, an irresistible dancer who is the “wealthiest girl in La Jolla.” Nawana, however, considers Taylor to be a stalker, but she’s trying to give him some “soul.” Despite Taylor’s professed interest in her, he really has his eye on two men: Joe Dallasandro, a newcomer who’s also trying to learn how to surf, and Tom Luau (Tom Hompertz), a local Hawaiian surfer. A subplot involves Ingrid Superstar, who might be two months pregnant, and Viva’s attempts to find her a husband, even though Ingrid already has a steady boyfriend, Eric Emerson, who admits that his three previous marriages were a way of compensating for his homosexuality.

In one memorable scene, Taylor sings a song to a baby whom he holds in his arms. Viva complains to Joe that Taylor is not a caring parent. After she takes the infant from him, Taylor suggests that if he and Joe have a baby, he’ll be better, to which Viva mockingly replies, “In whose womb?” We hear the sound of motorcycles outside, which causes her to launch into one of her infamous tirades: “Damn motorcycles out there. The whole neighborhood’s going to pot. First they let the hippies in. Then they let the motorcyclists in. The next thing you know we’re going to have the Ku Klux Klan racing down the streets.” As Viva scoops up another child, the baby suddenly slips out of her arms, but Joe somehow miraculously manages to catch the falling infant. Obviously ruffled, Viva blames Taylor, who quickly retorts, “You were nearly a complete failure as a mother.”

Warhol films are notorious for their unpredictability. The near catastrophe of the baby slipping out of Viva’s arms, in many ways, epitomizes that element. Yet it contrasts with the staged quality of the inhibited Tom Hompertz pretending to urinate on Taylor Mead later in the film – an act that was accomplished through editing. It represents one of the few instances in Warhol films that seems to runs counter to everything his films seemed to stand for. In the scene, Taylor lies on a surfboard and begs Tom to urinate on him. Tom discreetly takes down his pants and stands up, so that the framing only shows his legs. While Taylor pretends to masturbate and squeals about suffering and the cruelty of surfers, his face is sprayed with a foamy liquid (beer). Taylor is clearly ecstatic at what he considers to be his initiation into surfing and insists that he’s “a real surfer now.”

Warhol seemed well aware of the shortcomings of San Diego Surf. He wrote: “Everybody was so happy being in La Jolla that the New York problems we usually made our movies about went away—the edge came right off everybody.” Interestingly, he adds: “From time to time I’d try to provoke a few fights so I could film them, but everybody was too relaxed even to fight. I guess that’s why the whole thing turned out to be more of a memento of a bunch of friends taking a vacation together than a movie. Even Viva’s complaints were more mellow than usual.” Joe Dallesandro has suggested that there wasn’t a very clear idea for the movie prior to filming. Looking at the material, it’s hard to imagine how the film could have been interesting given its narrative premise and lack of a central core. Victor Bockris attributes the film’s failure to the influence of Paul Morrissey. He indicates that Viva appealed to Louis Waldon “to beat the shit out of him and save this film from his cheap commercial tricks.”

San Diego Surf is a surfing movie that doesn’t show feats of surfing or, for that matter, even big waves. That might sound Warholian on some level, but here it works against the film for the simple reason that the shots of the ocean are merely intercut with the narrative. Warhol wasn’t interested in fidelity to genre expectations per se. After all, he worried that Horse, which was shot in the Factory, was too much “like a real Western.” Like Horse, San Diego Surf could have been shot entirely in the Factory. But because the film is shot on location, audience expectations change. In Lonesome Cowboys, the pop-top cans of soft drink, sounds of airplanes, filtered cigarettes, allusions to Superman, and so forth, announce the film’s contrivance, whereas San Diego Surf actually pretends to be something that it’s not. Warhol must have realized this because that certainly wasn’t the case with his next film, the notorious Blue Movie, in which Viva and Louis Waldon don’t pretend, but actually engage in sexual intercourse on camera.

San Diego Surf is not without interest in Warhol’s film career. It’s a transitional work. Although it lacks Warhol’s patented strobe cuts, idiosyncratic framing and camera movement, the film nevertheless features many of his most famous later superstars: Viva, Taylor Mead, Louis Waldon, Joe Dallesandro, Eric Emerson, Ingrid Superstar, as well as Tom Hompertz. For me, even a minor or unsuccessful Warhol film contains aspects that make it intriguing to watch. Warhol’s films were high-wire acts that contained the risk of possible failure, which was a crucial element of his conceptual and aesthetic approach to film. You have to respect Warhol for that. Most filmmakers simply aren’t that daring.

Note: For more detailed coverage of Andy Warhol’s films, including the sexploitation films and San Diego Surf, please see my new book The Black Hole of the Camera: The Films of Andy Warhol (University of California Press, 2012).

Taylor Mead, Viva, Joe Dallesandro, and Paul Morrissey recall the making of San Diego Surf in Interview.