Harmony Korine has tried really hard to be America’s most vilified filmmaker. He wrote Kids (1995) for Larry Clark at age nineteen, which made $7 million at the box office and gave him credentials within the industry. With $1 million from Fine Line, his own debut feature, Gummo (1997), turned his hometown of Nashville (masquerading as southern Ohio) into what most people thought was a fictional freak show. Critics were not amused. Janet Maslin declared it the worst film of the year in the month of October, and even J. Hoberman had only derogatory things to say. Pitched to the youth crowd, the film grossed only slightly more than a tenth of its budget. Julian donkey-boy (1999), Mister Lonely (2007) and Trash Humpers (2010) didn’t fare much better at the box office. Until now, Korine has been more interested in creating individual scenes, so it’s no wonder that his films garnered fans but not a wide audience. In a sense, Spring Breakers was probably do or die for Korine career-wise, so it’s truly amazing that he has managed to create a major hit with his exploitation fantasy of young college women gone bonkers.

I doubt that Korine has first-hand experience with the American college ritual known as “spring break.” He was instead associated with street culture and the graffiti art scene that sprang from Aaron Rose’s Alleged Gallery on the Lower East Side of New York City. Underneath the trippy and colorful opening credits of Spring Breakers, we hear sounds of the ocean, gulls, and squeals of young kids enjoying the surf. This is followed by a prolepsis. In slow motion, we see gyrating bodies of college students with arms raised victoriously in the air. Young women shake their asses at the camera and expose their bare boobs, doused in beer, while the young men use cans and bottles of the same liquid to simulate peeing into the open mouths of coeds beneath them. College guys grab their crotches like rappers, a group of women suck on rainbow popsicles suggestively, while a number of both men and women stick out and wiggle their tongues, or flash us the middle finger as they jump in the air ecstatically.

The film cuts to black, after which we see two college women, Candy (Vanessa Hudgens) and Brit (Ashley Benson) smoking bongs with two guys, while a third woman with streaks of pink in her hair, Cotty (Rachel Korine), lies passed out on the couch. Following this, we see typical images of students on a small southern college campus. Brit and Candy sit in a darkened lecture hall, where Candy draws a pictures of a penis and simulates oral sex, while tuning out the professor’s lessons about civil rights and the black freedom struggle. Meanwhile Faith (Selena Gomez), sits cross-legged in a born-again Christian group presided over by a guy, who claims to be crazy for Jesus. A couple of believers later warn Faith to stay away from her friends, especially Brit and Candy, but Faith counters that she’s known them ever since grade school. Our four female protagonists are bored with college. In their minds – and this is a hilarious conceit – going on spring break will be a transformative event that will somehow forever change their lives. It will be, but in ways they can hardly anticipate.

The women actually don’t have enough cash to go on spring vacation, but that doesn’t stop them. Three of them – Cotty, Brit, and Candy– rob the car of one of their professors. In order to jack up their adrenaline, they scream, “Just fucking pretend you’re in a video game, act like you’re in a movie or something.” Brit and Candy rob the local Chicken Shack, while Cotty watches from the getaway car. Dressed in black ski masks and carrying a small sledgehammer and squirt guns that look like the real thing, the two women violently smash plates and terrorize the patrons (the black ones fork over their wallets, while being careful to show no visible reaction). After setting the vehicle on fire, the three return to the dorm with wads of dough. Faith is initially shocked, but seeing all the money excites the women sexually. Cut to a shot of the Sunshine Skyway Bridge in St. Petersburg, Florida, and then shots of the four of them inside a bus of rabid partygoers.

Spring break is one endless party after another, as the four coeds join in the fun, which includes getting drunk and high with the anonymous throngs of college kids that fill the motel rooms, balconies, swimming pool, and sandy beach. Everyone partakes of the bongs that get passed around, snort lines of cocaine, and act generally obnoxious. Faith’s phone call to her Grandma bears no resemblance to the images we see on the screen: excessive drinking, drug taking, girl on girl smooching, and grinding flesh. Instead, Faith describes spring break as “the most spiritual place she’s ever been” – magical and beautiful, and full of new friends from all over. She wants to come back next year and even hopes her grandmother can join her. “It feels as if the world is perfect,” Faith tells her, “like it’s never going to end.”

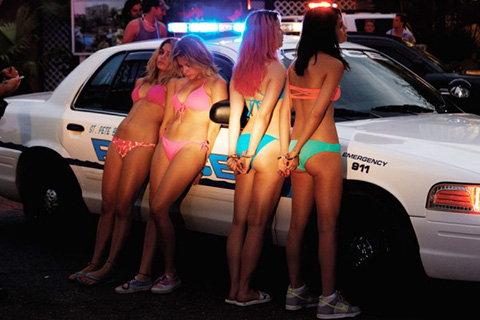

It doesn’t take long for the four women to get arrested by the police who cart them off to jail in their skimpy bikinis. Facing a huge fine or additional jail time, the women are bailed out by a demented white rapper named Alien (James Franco), who sports silver teeth, corn-rows, tattoos all over his body, and talks like he’s a gangsta. We see him and his sidekick (Russell Curry, aka Dangeruss) perform his hit song “Hangin’ with da dopeboys!” for the spring breakers earlier, but he and his twin skinhead associates (who likewise have silver teeth) also run a huge drug operation. Alien takes to these pretty young women, especially Faith, but Alien clearly freaks her out. “This is not what I signed up for,” Faith says tearfully, once Alien makes her play pool in a smoky room with a bunch of black thugs. As she cries, she tells the others, “We don’t know these people and I don’t know this guy and I just want to go home.” Remembering her bible study lesson that Jesus provides a way out when faced with temptation, Faith abruptly abandons her spring romp, and, to our surprise, exits the movie.

Faith is right about one thing: Alien is one crazy dude. As he tells them when they are released on bail, “Truth be told, I ain’t from this planet, y’all.” In his mansion, he brags to the women about having gobs of money, an arsenal of weapons, and a house filled to the brim with material possessions. “Look at my shit” he keeps repeating, as if it’s a mantra. He claims to be living the American Dream, and driving around town in his white sports convertible with sexy coeds clad in bikinis is, for him, its fulfillment. To Alien, life suddenly feels like a dream. At magic hour one evening, the three women, dressed in pink ski masks, demand that he play them something sweet and uplifting. He responds, “Oh, y’all want to see my sensitive side.” He sings a song by Britney Spears, whom he describes as “a little-known pop star,” and “one of the greatest singers of all time, and an angel if there ever was one on this earth.” While the women pirouette and dance with raised assault weapons, Alien does a rendition of “Everytime” on a white piano at water’s edge.

But Alien’s blissful fantasy, like spring break, is a temporary bacchanal that can’t last. Indeed, it turns out that Alien and his gals become engaged in a drug and race war with a black criminal named Big Arch (played by rapper, Gucci Mane). We know from Chris Fuller’s Korine-inspired Loren Cass (2009) that St. Petersburg has a history of racial tension. It was the scene of race riots in 1996, when Fuller was growing up there. The narrator of Fuller’s film intones: “St. Petersburg – a dirty, dirty town, by a dirty, dirty sea because the soul of the railroad is the chain gang.” This side of St. Petersburg is not much in evidence to the spring breakers who temporarily flock there, but the town is apparently too small to accommodate both Alien and his former childhood friend and mentor, Big Arch, who tells his associates: “He’s taking food out of my baby’s mouth. My baby’s hungry. My baby needs to eat. My baby’s starving. And we’re going to do something about it.”

True to his character’s name, James Franco’s performance is out of this world. In pushing his character to such an extreme, he toys with psychodrama, in ways that recall Harvey Keitel in Bad Lieutenant (1992) or Nicholas Cage in Vampire’s Kiss (1989). Franco’s portryal of Alien teeters on the verge on caricature, but it’s the rapper’s vulnerability that makes him such an endearing character. The four college women, especially Selena Gomez, are great as well. John Waters wrote about Spring Breakers: “The best sexploitation film of the year has Disney tween starlets hilariously undulating, snorting cocaine, and going to jail in bikinis. What more could a serious filmgoer possibly want?” Yet Korine takes an exploitation film that displays women’s bodies and inflects it with a decidedly feminist twist. Spring Breakers may be a barrage of glitz and allusions to pop culture, but it has substance, as well as a cockeyed sense of humor. It’s totally fitting that the last image of the movie is upside down.

Spring Breakers goes well beyond being a play on genre. The film’s fragmented and elliptical style eschews linearity in favor of collage. Korine’s play on time mixes future, present, and past – fantasy and memory and dream – into his own version of drug time and a subjective mental state, as shots and snippets of dialogue repeat, images destabilize and contort into amorphous swirls of grainy color, time shifts, moods change, and our sense of reality gets confused and threatens to break down. Thanks to Benoît Debie’s awesome cinematography, the film is so awash in psychedelic and fluorescent colors that watching Spring Breakers really feels as if someone slipped you a hallucinogen.