As a child I lived only a block from Marie Menken, so that might explain why I always have had a tender spot in my heart for this major pioneer of American avant-garde cinema. Marie and her husband Willard Maas lived in a penthouse apartment at 62 Montague Street in Brooklyn Heights. Menken is the subject of Martina Kudláček’s documentary, Notes on Marie Menken (2006), a biographical portrait of this largely neglected figure. The film is now available on DVD.

Marie Menken was an extremely tall and imposing woman. There’s a famous photo of her dancing with Tennessee Williams, in which she towers over him. Like Jonas Mekas, she was also from Lithuania. Menken was married to the poet/filmmaker Willard Maas, who was gay. They met at the artist’s colony Yaddo and married in 1937 – it was his second marriage. In Film at Wit’s End, Brakhage tells the story of first meeting the two of them, in which Maas gets into a fistfight with his lover, Ben Moore, and ends up a bloody mess in the snow.

Marie and Willard had a very difficult life together. As a couple of interviewees note in Kudláček’s film, they are reported to be the model for Edward Albee’s well-known play, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf – after he had occasion to observe their constant fighting. The couple lost a child and proceeded to torture each other over it for the rest of their lives. Marie was accepting of Willard’s gayness and befriended his many lovers. Together they started Gryphon Films. Brakhage, Charles Boultenhouse, and Gregory Markopoulos were associated with Gryphon, which represented an important early attempt at cooperative filmmaking. Marie supported herself for thirty years by working the graveyard shift at Time Magazine.

Marie was the camerawoman for Maas’s Geography of the Body (1943). She was the technical person, not Maas, which was the opposite situation of Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid. Her first film was Visual Variation on Noguchi (1945), but she didn’t make another, Glimpse of the Garden (1957), for another twelve years. Menken made small, highly personal and lyrical films. Among them are: Hurry, Hurry (1957, Dwightiana (1959) Eye Music in Red Major (1961), Arabesque for Kenneth Anger (1961) Bagatelle for Willard Maas (1961), Mood Mondrian (1961), Notebook (1962-63), Go Go Go (1962-64) Wrestling (1964), Lights (1965) and Andy Warhol (1965). Many of them are interspersed throughout Kudláček’s richly evocative portrait of Menken.

Menken exerted a major influence on other avant-garde filmmakers. Brakhage acknowledged that he owed her an tremendous debt and claimed she gave him the courage to be completely free with the camera. Menken was overshadowed by Maas (who is now forgotten), even in the early issue of Filmwise devoted to them. Maas apparently ridiculed her filmmaking efforts. She didn’t appear in the first edition of P. Adams Sitney’s Visionary Film – an oversight he later corrected. Even Maya Deren reportedly only respected Marie as a painter, but not as a filmmaker. Although Menken never received the credit she deserved during he lifetime, her work is included as part of the permanent collection of Anthology Film Archives, which is where I first saw her magnificent films.

Why was she ignored? One reason no doubt has to do with sexism. At the time Menken worked, there were less than a handful of women filmmakers. The heavily symbolic “trance” films were very much in vogue. In the context of the high seriousness of a more literary poetic cinema, Menken’s more playful and painterly films were simply an anomaly. In Notes, Jonas Mekas, who gave Menken her first film show at the Charles Theatre, observes that they contained “no big action, nothing spectacular, no unusual content.” Menken’s work is visually poetic. She pioneered the autobiographical diary film – a tradition that includes such filmmakers as Brakhage, Jonas Mekas, Peter Hutton, Warren Sonbert, Andrew Noren, Nathaniel Dorsky, Madeleine Gekiere, as well as a host of others.

Menken was also a painter. She had a one-person show at Betty Parsons Gallery in 1949, but we learn from Alfred Leslie in Notes that John Bernard Myers later regretted giving her a show at Tibor de Nagy gallery in 1951 because her work “lacked edge.” According to Roger Jacoby in an old issue of Film Culture, all or most of her work was destroyed by a flood at her loft on Baltic Street, and by theft. Menken and Maas knew all the artists, the beautiful people, including Marilyn Monroe, Arthur Miller, Richard Wright, and Truman Capote. Menken and Maas were notorious for their parties. They would invite all the celebrities, so it’s easy to see why Menken would connect with the Warhol crowd.

In POPism, Warhol says he met Marie Menken and Willard Maas through the surrealist poet Charles Henri Ford, who was a close friend of Parker Tyler, the film critic, who edited View magazine in the 1940s. Ford is the one who suggested Gerard Malanga as an assistant to Andy Warhol. Malanga’s high school English teacher was the poet Daisy Aldan. Through Aldan, Malanga was invited to a party, where he first met Maas, who taught at Wagner College in Staten Island, where, not coincidentally, Malanga wound up a student. At the very end, Marie and Willard were hopeless alcoholics. Marie and Willard died within days of each other.

Both Willard and Marie appeared in Warhol’s films. Willard’s major part was offscreen. He is rumored to be the guy giving head to DeVerne Bookwalter in Warhol’s infamous Blow Job (1964). Marie played Fidel’s rebellious sister, Juana, in the Warhol-Tavel collaboration, The Life of Juanita Castro (1965), in which cold war politics are portrayed as stemming from family squabbles and incidents from childhood. Marie becomes inebriated during the course of the film, which causes her to rebel against her brother Fidel and having to repeat Tavel’s dialogue verbatim. Menken is absolutely wonderful, as she butchers Tavel’s language, makes snide asides, and manages to epitomize the contrarian personality of Fidel’s sister. Marie also played Gerard Malanga’s mother in a scene in The Chelsea Girls (1966), where Marie puts on a frightening and sadistic display, as she rails against her son, while cracking a whip.

Martina Kudláček’s portrait isn’t really an in-depth scholarly documentary that has unearthed a lot of new facts and information on Menken. It’s more like a primer on her life and films in a similar manner to Jennifer M. Kroot’s homage to George and Mike Kuchar, It Came from Kuchar. Kudláček’s approach actually fits her subject matter in employing its own quiet poetry, such as when she focuses on the peeling paint of the rusty radiator in Alfred Leslie’s loft.

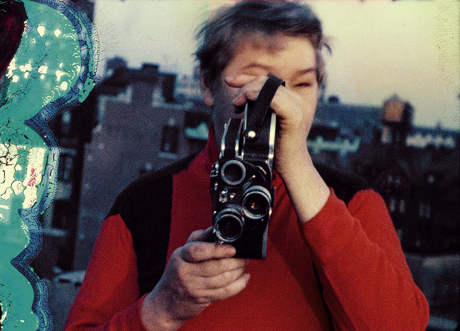

Kudláček has assembled a noted group of prominent individuals to talk about Marie Menken’s life and work. We hear Brakhage lecturing about Menken’s aesthetic in his booming voice. Peter Kubelka demonstrates her technique as reflecting the inherent properties of a Bolex camera in Go Go Go, which he demonstrates for us, complete with sound effects. Kenneth Anger tells about assisting Menken in making the film that became Arabesque for Kenneth Anger. He talks about her uncanny ability to edit in-camera as she filmed, noting that “she had a feeling for movement and rhythm that was like a dancer.” Anger indicates that Menken had a “halo around her head.” Anger also points out that if it wasn’t for staying at her place in Brooklyn, he would have never made his underground classic Scorpio Rising (1964). Billy Name (Linich) compares Marie to the legendary Tugboat Annie.

Gerard Malanga discovers new footage of Marie Menken and Andy Warhol in which the two of them have a duel with Bolex cameras. The filmmaker and secret archivist in me cringes as Malanga opens an old rusty film can found in storage and uses hand rewinds to run the original footage through an old Moviescope viewer. What could be any harder on such priceless historical footage? Gerard later playfully criticizes Marie for underexposing some footage by not using a light meter.

Malanga is given considerable time in Notes for Marie Menken. He and Kudláček take a field trip out to visit Gerard’s estranged father’s vault and Marie’s grave. Gerard discusses the fact that Menken wanted to adopt him as a son, except that he already had a living mother. Malanga is unsure whether he really wanted Maas as his surrogate father. Kudláček also interviews Mary Woronov, who exudes her usual enthusiasm as she describes the harrowing scene with Marie in The Chelsea Girls, in which Mary plays Gerard’s sullen girlfriend.

The most poignant scene in Kudláček’s film, however, involves Jonas Mekas. To the credit of Kudláček and her editor Henry Hills, they keep the most riveting footage for the end. What’s fascinating is that Jonas, who’s appears to be a bit tipsy from drinking, decides to tell a remarkable story about Marie. First off, he addresses and toasts the filmmaker, Martina, by name. Jonas rubs his mouth, snorts several times, clears his throat, and waves his arms, upsetting the camera placement and framing before he shifts into “interview mode.”

In his heavy accent, Jonas begins, “I do not remember how I met Marie and Willard.” He hesitates, then remarks, “Her films were like . . . about nothing . . . little feeling, little emotion, little image.” He talks about pre-Christian Lithuanians being pantheists. Mekas suggests that Marie Menken’s work conveys a sense of nature – “flowers and trees and moon and the sun.” Jonas talks about how initially he didn’t know Menken’s ethnic origin, but one day he heard her singing a Lithuanian children’s song. Although the lower part of his face is cut off by the framing, Jonas sings the actual song for us.

Jonas then attempts to explain the lyrics. Haltingly, he translates: “Little girl, I’m like a little rose, like a lily in the flower garden.” He rubs his mussed hair and sweaty face, and rocks forward and backward in the frame He comments, “It’s another variation of how to attract [he moves his fingers] a young man.” Jonas suddenly sings in English, “I must know, I must know how to attract a young man. I must know, I must know, how to attract a young man.” Jonas laughs and remarks, “That’s a funny song, no?” As Jonas indicates it’s been a hard day and tries to regain his composure, Kudláček cuts to a shot of lily pads. Jonas laments, “There was so much love there. Poetry, and love, and cinema.” Sadly, he toasts, “Oh, Marie.”

The film cuts to scene where Marie’s nephew plays audio tape of her singing boisterously over footage of a performance involving people with umbrellas on the boardwalk. A hand rewinds Marie’s film footage, leaving the blank white screen of a Moviescope. Most documentaries depend on creating some type of intense dramatic conflict, but Kudláček’s portrait of Marie Menken is rooted in something far more basic. Like Menken’s films, Notes on Marie Menken is infused with intense love for its subject. “Oh, Marie . . .”