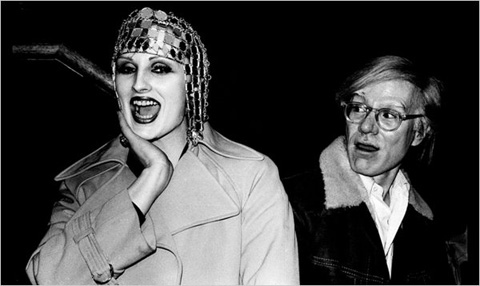

[Photo by Anton Perich]Candy Darling (1944-1974) was a later Warhol superstar from the period after the Pop artist was shot by Valerie Solanas and became the producer of Paul Morrissey’s films. Born James L. Slattery, Candy appeared in Flesh (1968-69) and starred in Women in Revolt (1971), Morrissey’s satire of the women’s liberation movement – a film that parodied Solanas and the SCUM Manifesto in every way imaginable. James Rasin’s poignant documentary about the tragic life of Candy Darling, Beautiful Darling, opened in Manhattan last week. It joins the growing list of documentaries about Warhol performers and associates, such as Nico Icon, Pie in the Sky: The Brigid Berlin Story, Jack Smith and the Destruction of Atlantis, and A Walk into the Sea: Danny Williams and the Warhol Factory. For true Warhol fans, Beautiful Darling, is not to be missed.

In Women in Revolt, Holly Woodlawn and Jackie Curtis decide that they need to enlist real beauty to their feminist cause. They manage to rope Candy Darling into the PIG (Politically Involved Girls) movement. After she decides to become a movie star, Candy gets taken advantage of by an agent (Michael Sklar). By the end of the film, she has managed to sleep her way to the top, only to be exposed by a tabloid reporter, who brings up the dirt about her – the suicide of her parents, her incestuous relationship with her brother, and her sleeping with various directors to get parts in foreign films where she does very little. Alluding to the title of her new film, the columnist concludes, “I don’t think you’re a Blonde on a Bum Trip; I think you’re a Bum on a Blonde Trip.”

The former might better describe Candy’s actual life story. Beautiful Darling begins with Jeremiah Newton, Candy’s former roommate and the default executor of her estate, as he forges a certificate from the Garden State Crematory in North Bergen, New Jersey. After we watch her gravestone being transported, Candy appears in old footage and announces buoyantly: “Hi, I’m Candy Darling. I’m an actress here in New York. I’ve been in eight pictures – small parts in big pictures, and big parts in small pictures.” In the company of Jane Fonda, who hoped to land a part in a Warhol film, Candy, looking like some sort of fashion-crazed pirate, announces, “I call myself Candy Warhol now,” as everyone laughs uproariously.

The actress Helen Hanft describes how Candy managed to “fool” her father and uncle, who acted “very courtly” when they met her. We hear Lou Reed’s song “Walk on the Wild Side,” in which she was immortalized, along with Holly Woodlawn, Jackie Curtis, Joe Dallesandro, and Joe Campbell, aka the “Sugar Plum Fairy,” who appeared in My Hustler (1965). Candy shared Warhol’s love of movie stars. She sent a fan letter to Kim Novak, and was smitten by the missive she received back from the Hollywood actress. Fran Lebowitz views Candy as obsessed and living in the past, but Paul Morrissey claims that she was essentially a humorist, who was merely poking fun at stars.

Bob Colacello points to the paradox of Candy within Warhol’s more avant-garde circle, namely that she was a throwback to another era when the movie studios still existed. Gerard Malanga, however, claims that Candy was “very avant-garde in terms of who she was and how she invented herself.” Despite the juxtaposition of the two contrasting views, in a sense, Colacello and Malanga are talking about two different things. Colacello is discussing Candy as a performer, whereas Malanga is referring to Candy’s choice of sexual identity. To Glenn O’Brien, Candy, like Warhol, was her own artwork. The film cuts to footage of Candy at Warhol’s retrospective at the Whitney in 1971, where they both have great fun by putting on the press – a Warhol trademark.

Cloë Sevigny’s readings from Candy’s diaries represent some of the most compelling material in Beautiful Darling. The sense of gender difference that Candy felt early on led her to turn to the fantasy world of movies – James Slattery aspired to become a female movie star. Whereas Malanga indicates that “there was nothing fragile about Candy,” underground film star Taylor Mead describes Candy as “too gentle . . . too gentle for the bullies.” Newton met Candy when he was only 15-year-old. A devoted fan, he began his own audio diary after Candy’s death. Newton interviews a bigoted childhood friend. Once the person discovered Jimmy Slattery in drag on the Long Island train, she refused to have anything to do with him again and thought “he should be put away.” It’s a response indicative of the times.

Holly Woodlawn explains the dangers that cross dressers experienced in the 1960s before Stonewall, where men could be arrested for wearing woman’s clothes in public. Through Jackie Curtis, Candy, who went by the name “Hope” at the time, became involved in theater, which is where Warhol first saw her in Glamour, Glory and Gold. Holly describes Candy as attracting a coterie of groupies. She includes Newton among them, whereas Sam Green, who curated Warhol’s infamous early show at the ICA in Philadelphia, describes him as kind of her “younger brother” – someone who was merely star struck by her incredible beauty. Newton doesn’t deny that hanging around with Candy brought him acceptance with the hipsters at the Factory and eventually at Max’s Kansas City, where Candy, Jackie, and Holly held court in the back room.

Colacello discusses the early 1970s as a period when “a surge of Hollywood nostalgia came in.” He adds, “And Candy was right in there, somewhere between the past and the future.” John Waters comments, “She was like a real movie star from MGM . . . only in a world that was filled with LSD, and speed really.” Warhol mentions that Candy and the others weren’t really drag queens because they actually believed they were women. Jayne County insists on the fact that Candy was a transgender person. Friends seem unclear about her actual romantic relationships. Melba LaRose, Jr. mentions that Candy was in love with Gerard Malanga, who responds with surprise: “I’m flattered. I didn’t know that.”

Candy claims that she never had to pay for anything, but the truth is that Candy lived hand-to-mouth, as her diaries clearly indicate. When it’s suggested that she had to do certain things to get money, Jeremiah becomes indignant, even if his own interviews provide contrary evidence. We see rehearsal footage for Women in Revolt (so much for Morrissey’s claims about improvisation), along with the trailer, with praise of her highly theatrical performance from both John Waters and Paul Morrissey. Candy eventually appeared as Violet in Tennessee Williams’s Small Craft Warnings at the time when the playwright’s own career was in free fall.

Along with starring in Women in Revolt, this marked a highpoint in Candy’s career. Her success proved short lived. Penny Arcade explains, “And then all of a sudden, it turned out to be this ephemeral thing, and the carnival had moved on.” Shortly after this, while staying at the Diplomat Hotel, in June 1973, Candy felt abandoned and alone. She writes: “All I know is: I love, and I am not loved. I do not know happiness. I know despair, loneliness, and longing. My biggest problem is I have no man to love me. So nothing else matters or makes much of a difference.”

More and more, Candy’s gender issues made her feel as if she were “living in a veritable prison.” There’s no question that Candy Darling was gorgeous, but beauty didn’t translate into love (especially for a transgender individual), just as her limited fame as performer didn’t translate into enough money to eat properly or pay the rent. Rasin’s documentary makes the most of its archival material, even if, structurally, Newton’s burial of Candy’s ashes in Cherry Valley, New York seems a contrivance for the sake of the film.

After Candy discovered she had a cancerous tumor, most people felt she accepted her fate as a final role to play. Lebowitz discusses Peter Hujar’s famous picture of Candy on her death bed. Candy staged the way she wanted to appear in the photo – a beautiful actress dying in her prime. Over the final photographs of Jimmy Slattery as a young boy, including a very sweet one of him wearing a woman’s wig, which reminded me of Jonathan Caouette’s Tarnation (2003), Sevigny reads from Candy’s diary: “I will not cease to be myself for foolish people. For foolish people make harsh judgments on me. You must always be yourself, no matter what the price. It is the highest form of morality.”