Born in Vicksburg, Mississippi, Charles Burnett grew up in South Central Los Angeles, the scene of the 1965 Watts Riots in which thirty-four people were killed and over a thousand people were injured. Burnett was part of a group of African-American filmmakers – Haile Gerima, Julie Dash, and Billy Woodberry – who came out of the UCLA film program during the blaxploitation years of the 1970s. While completing his MFA degree, Burnett received the Louis B. Mayer grant for the most promising thesis film, which became Killer of Sheep (1977). The film remained largely unseen by the general public for several years, and soon after became nearly unavailable (due to copyright issues) despite its strong critical reputation and official landmark status. Originally shot on 16mm black-and-white film, Killer of Sheep has been restored and blown up to 35mm by Milestone Films. Thirty years after the fact, Killer of Sheep finally received a belated theatrical release, grossing over $400,000 domestically at the box office, a very respectable figure for an indie re-issue. The long-awaited DVD version of the film, which includes Burnett’s re-edited second feature My Brother’s Wedding (1983) will be available on November 13. Along with the earlier DVD release of Gus Van Sant’s Mala Noche, this is a cause for celebration for anyone interested in the history of American independent film.

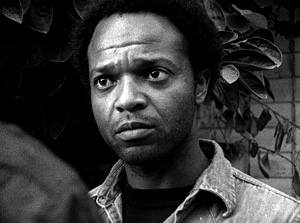

In my book on independent screenwriting, Me and You and Memento and Fargo, I discuss variations on the conventional goal-driven protagonist by analyzing what happens when screenwriters employ passive (Safe) or ambivalent (Stranger Than Paradise) protagonists, or when they shift the protagonists midstream (Fargo). The protagonist of Burnett’s Killer of Sheep, who works in a slaughterhouse, is closest to Safe’s Carol White when it comes to the issue of agency. As a result of being subjected to the everyday horrors of his environment, Stan suffers from insomnia, impotence, and a growing sense of depression about his dead-end life. Killer of Sheep begins with a flashback from Stan’s childhood, in which he is yelled at for not defending his brother in a fight. His father insists he’s not a child anymore and that he better start understanding what life’s about. Stan also gets slapped across the face by his mother. But Stan (played by Henry Gayle Sanders) turns out to be less a fighter than a weary survivor. He’s so beaten down by life’s daily grind, especially by the dehumanizing effects of his job, that Stan suffers from inertia. Given the social milieu that Burnett portrays, it’s not hard to understand why. Killer of Sheep depicts the physical violence and the sense of despair and hopelessness that pervades life in the ghetto. It provides a glimpse of a world many viewers don’t know anything about, especially because we’re never given an opportunity to see this type of representation in mainstream Hollywood cinema

When Stan complains to Oscar early in the film that he’s working himself into his own hell – he can’t sleep at night and doesn’t have peace of mind – his friend responds, “Why don’t you kill yourself; you’ll be a lot happier.” Stan later presses a warm cup of coffee to his cheek and suggests that it reminds him of making love to a woman., but another friend, Bracy, pokes fun at Stan by remarking, “Myself, I don’t go for women who got malaria.” As Stan struggles against the travails of his day-to-day existence, various threats surface. The unattractive white female owner of the liquor store tries to proposition Stan by offering him a job, but Stan worries about the danger of getting shot in a holdup. Two acquaintances, Scooter and Smoke, attempt to get Stan to accompany them in some type of criminal activity involving murder. When Stan’s wife (Kaycee Moore) overhears them, she confronts the two men:

STAN’S WIFE: Why you always want to hurt somebody?

Scooter looks around to see if she might be talking with someone else.

SCOOTER: Who me? That’s the way nature is. I mean, an animal has his teeth and a man has his fists. That’s the way I was brought up, god damn me.

SMOKE: Right on.

SCOOTER: I mean, when a man’s got scars on his mug from dealing with son of a bitches everyday for his natural life. Ain’t nobody going over this nigger, just dry long so. Now me and Smoke here, we’re taking our issue. You be a man if you can, Stan.

STAN’S WIFE: Wait! You wait just one minute! You talk about being a man and standing up. Don’t you know there’s more to it than with your fists, the scars on your mug, you talking about an animal. Or what? You think you’re still in the bush or some damn where? You’re here. You use your brain; that’s what you use. Both of you nothing ass niggers got a lot of nerve coming over here doing some shit like that.

Scooter’s equation of masculinity with violence takes on bitterly ironic overtones because Stan’s job and depression cause him to lose his sexual drive, driving an emotional wedge between him and his wife. Stan’s wife short-circuits Scooter and Smoke’s attempt to involve Stan in their murder plans, but the scene underscores the constant temptations for someone like Stan, who denies his own poverty by claiming that he gives things to The Salvation Army and by comparing himself to other less fortunate neighbors. Stan tells Bracy: “We may not have a damn thing some time. You want to see somebody that’s poor, now you go around and look at Walter’s. Now they be sitting over an oven with nothing but a coat on, and sitting around rubbing their knees, all day eating nothing but wild greens picked out of a vacant lot. No, that ain’t me and damn sure won’t be.”

This discussion of poverty actually causes Stan to make one proactive attempt to take action, which provides the only semblance of a plot thread in an otherwise impressionistic film consisting of a series of vignettes. Right after this, he tells another friend, Gene, who wants to better himself by getting a car, “Tomorrow after I cash my check, let’s go over to Silbo’s and buy that motor and put it in.” True to his word, Stan cashes his check at the liquor store, and he and Gene show up at Silbo’s to dicker over the price of the motor. While there, Silbo’s nephew lies on the floor with a large white bandage wrapped around his head. When Gene asks what happened, it turns out that two men beat him up, and one kicked him in the face. After Stan asks why, the man answers, “He didn’t have nothing else to do with his hands and feet, nigger.” The nephew later makes crass sexual remarks to a woman named Delores, whose later response – “You about as tasteless as a carrot” – turns out to be one of the best lines in the film. Delores follows this by also kicking the injured man in his head. In the midst of the ensuing ruckus, Silbo agrees to take fifteen dollars for the motor.

Stan and Gene lug the heavy motor out of the house, down the wooden stairs, and eventually place it in back of the pickup truck. Gene injures himself in the process and refuses to secure it any further. He insists it will be fine. After the two men hop inside, the truck lurches backward rather than forward, causing the motor to fall off. Stan and Gene get out, realize that the block of motor is now cracked, and simply leave it there. We watch a little girl’s face pressed up against the rear window of the truck cabin. The camera moves in closer and then pulls away from the motor, which remains where it has fallen in the street.

This sudden flattening of a dramatic arc is mirrored again toward the end of the film when Gene finally gets his car running and they all set off for the racetrack. Their expectations, however, quickly get deflated when the car develops a flat tire and Gene doesn’t have a spare. Bracy raps: “Man, I’m out here singing the blues, got my money on a horse can’t lose, and you’re out here on a flat. I always told you to keep a spare, but you’s a square. That’s why you can’t keep no spare. Now how are we going to get there, huh?” All of them get back into the car. A number of critics – from Armond White and Michael Tolkien to J. Hoberman and Manohla Dargis – have discussed Killer of Sheep in terms of Italian neo-realism, but I don’t find the comparison totally accurate. Films, such as Rossellini’s Open City or DeSica’s Bicycle Thieves – two films often cited as influences – have strong dramatic arcs, whereas Burnett either ignores or undercuts them. Like many independent filmmakers, such as Jim Jarmusch in Stranger than Paradise, Gus Van Sant in Mala Noche or Allison Anders in Gas Food Lodging, Burnett is less interested in creating dramatic tension than in characterization. Burnett’s real focus is on creating a portrait of Stan’s life within this particular social milieu. Nothing changes in the course of the film for Stan, so that his character lacks an arc as well.

Throughout Killer of Sheep, Burnett continually draws a comparison between the fate of the neighborhood children and the slaughter of sheep. After the initial flashback, the film shifts to the present, where Stan’s son, Stan Jr., ducks behind a wooden shield, as rocks ricochet off it. The kids engage in a full-fledged rock fight. One of them appears to get hurt, but after a brief pause, the fighting erupts again. The next shot is from a moving train as the kids hurl rocks at it. Burnett depicts a barren landscape of dust and dirt and almost no vegetation, except for occasional palm trees. The kids play on a train, pretending to push the one of the cars on top of a kid lying on the tracks. In the neighborhood of South Central, even play has become a constant battleground. When Stan Jr. later returns home, he sees two guys stealing a TV set. Stan Jr. tells them that the well-dressed man we see standing there is going to call the police. This suggests that Stan Jr. is already at risk in terms of his identification with the perpetrators of the crime rather than the victim.

When we first meet his father, Stan, he’s busy doing home repair work. In this scene, his daughter, Angela, wears a huge dog mask, which seems to reference Helen Leavitt, Janice Loeb, and James Agee’s classic documentary, In the Street. When a friend asks him when he last went to church, Stan answers not since “back home.” The suggests the effects of dislocation that African Americans have experienced as a result of the migration from the rural, agrarian South to urban centers such as Los Angeles – a subject that Burnett would explore in his later film To Sleep With Anger (1990). In a mean gesture, Stan Jr. scrunches his sister’s dog mask before running off. Stan’s two other friends also poke at the little girl’s mask as they walk by. Angela goes outside and hangs on the fence with her hand in her mouth, while a little boy stands nearby. Such a scene is thematically evocative, but doesn’t advance the narrative in any conventional way.

In the overall structure of Killer of Sheep, poetic details, such as Angela wearing the dog mask, are given equal weight in the narrative. The script for the eighty-three minute film is only about seventeen pages long, suggesting that Killer of Sheep relies primarily on visual storytelling and contains very little dialogue. When we think of the Killer of Sheep, we remember its striking images, including those at the factory, where the Judas goats leads the sheep to slaughter. For instance, there’s the scene in which Angela sings off-key to a song by Earth, Wind & Fire, while she plays with a doll. Other scenes include: the kids trying to spin tops in the rubble; the scene where the older girls are dancing and the boy on the bike tries to act like a tough guy and they beat him up and he goes away crying; the dangerous shots from below of the kids jumping across the tops of buildings; the scene toward the end when Stan comes home from the factory and knocks over the two kids who are doing handstands and headstands. There’s also the scene where a man in a soldier uniform wants his clothes back, while a woman upstairs brandishes a gun, and her two young children sit on the couch nearby. This tense situation provides entertainment for the entire neighborhood, including Stan, who witnesses the incident while passing by.

There are scenes between Stan and his wife, which show her sexual frustration. In one, which reminds me of a scene from Stan Brakhage’s early trance film, Reflections of Black, Stan and his wife dance to music of Dinah Washington’s “This Bitter Earth.” For his wife, the dancing has an erotic charge, but Stan, who is shirtless, appears to be merely going through the motions. After the record ends, she attempts to engage in foreplay, but Stan extricates himself and leaves his wife standing alone against the sunlit window. In voiceover, we hear what sounds like a poem: “Memories that just don’t seem mine, like half-eaten cake, rabbit skins stretched on the back yard fences. My grandma, mot dear, mot dear, mot dear, dragging her shadows across the porch. Standing bareheaded under the sun, cleaning red catfish with white rum.” Stan’s wife picks up a pair of white baby shoes and presses them against her bosom, then exits the frame. The scene lasts nearly four minutes. After he returns from work later on, Stan, his wife and daughter are all together in the kitchen. His wife suggests to Stan that they go to bed, but Stan sits silently at the table while she clears the dishes. Angela comes over to her Daddy. She puts her arms around his neck. He looks at her lovingly, while Angela stares at her mother, who sits there despondently. Burnett ends the sequence by framing the shot from behind the wife, so that we watch Angela playfully touch her father’s face and then look over for her mother’s reaction.

The above scene is appropriately followed by the one of the little girl in the dress, who carefully places freshly laundered clothes on the line. Burnett cuts to a shot of a hole in a garage door. A boy crawls out, walks over, and spies on the girl. He returns to the hole, and four more kids of varying sizes climb out. Burnett cuts back to the girl, whose back is turned, and the boys throw dirt all over the clothes hanging on the clothesline. As she turns and stares, the camera holds on her haunting look, which parallel’s the one of both Stan’s wife and daughter in the previous scene. Burnett cuts from the young girl in the dress to shots of the Judas goats at the slaughterhouse.

Burnett usually composes a shot and then doesn’t cut unless it’s absolutely necessary, which results in a film that manages to take its sweet time. Besides its leisurely pace and episodic rather than dramatic structure, Killer of Sheep maintains the overall feel and texture of an independent film in other ways than its initial minuscule $10,000 budget. Its overall narration is much closer to international art cinema than classical Hollywood. Killer of Sheep employs symbolism and ambiguity – two characteristics of art cinema. Plot is also minimized in favor of the film’s densely layered visual imagery. The film’s central metaphor, reinforced by the title, would no doubt seem too obvious were it not made by one of America’s greatest film poets. This remarkable restored version allows viewers to see the film as Charles Burnett originally envisioned it, even if he lacked the necessary resources at the time. Killer of Sheep is quite simply one of the best first features ever made, as well as one of the true classics of American independent cinema.