The 2012 Wisconsin Film Festival began last Wednesday night with London filmmaker Ben Rivers’s Two Years at Sea (2011), his majestic feature-length portrait of an eccentric recluse named Jake Williams, whom he had filmed previously in a fourteen-minute short This is My Land (2006). The film documents and explores Jake’s isolated rural existence within the clutter and junk of a sprawling ramshackle dwelling in a forest in Scotland. Throughout the course of Two Years at Sea, we never see another human being, but hear sounds of sheep, cows, birds, and other wildlife.

It’s hard to know exactly what to make of Jake, as we observe him in his daily rituals: trudging through the snow from behind, sleeping in various places, bathing in a home-made shower, washing clothes, chopping wood, fishing on a primitive raft, listening to cassette tapes, reading a book, and so forth. There’s a story there, to be sure. Why does Jake live the way he does? Why has he chosen this type of existence? Rivers, however, has little interest in issues of conventional narrative, despite the fact that Jake looks at old photographs (there’s one of an attractive young woman; another of an older man; and an overexposed one of two kids) that hint at some type of missing back story.

In an interview with Michael Sicinski in Cinema Scope, Rivers explains: “Because the film is also a world, it’s something I want to exist in and of itself, rather than being about something. This all brings me to J.G. Ballard, one of my all-time favourite authors. His work is all about the transformation of landscape into something that somehow frees the central character from all their preconceived norms, a place that is consciously significant to every decision made about how one is living and proceeding through the mire.”

At times, we feel as if Jake might be the last human being left on earth. Yet, to me, the film feels less about the present or future or a self-contained world than a depiction of a present that’s nonetheless imbued with a strong sense of the past. Rivers shot the film in anamorphic 16mm film, which he hand processed in his kitchen sink. It was subsequently blown up to 35mm. There’s a sense that we’re viewing historical footage. It feels, at first, as if we’re back in the 1960s or early 1970s, observing an old hippie who has dropped out.

As the film progresses, however, there’s an odd sensation that we seem to be moving backward in time. The shots of Jake asleep in various locations and situations reminded me of post-mortems, those antique photos of loved ones preserved through photography. In one sequence, we watch as Jake makes a long trek over rugged terrain. In a wide shot, he walks toward the camera, carrying some type of rig on his head and four oblong plastic containers. Jake gradually blows up air mattresses and constructs a raft that he uses to fish in a loch. This shot of him fishing, which lasts nearly 7 minutes, is a key scene in the film’s trajectory back in time – as if we’ve suddenly been transported to the 19th century.

It’s difficult to make an intriguing film with a single character, especially if it’s going to be feature length. We watch Jake go through his daily chores, routines, and rituals, some of which seem to be of the filmmaker’s devising (this is a somewhat contrived or fictional quasi-documentary portrait), especially when he transforms an old camper into a sort of tree house. The shot shows the trailer, like a flying saucer, magically rising up in the frame to eventually perch atop trees. The artifice of how this is accomplished is deliberately withheld, which adds a sense of mystery. Throughout the film, Rivers focuses on formal shots of clouds moving through the sky, a thunderstorm, steam rising from a kettle on the stove, and a black cat who stares curiously at the camera.

Jake’s lifestyle nevertheless embodies the past. The film mimics this in a number of ways. It’s shot on film, for one thing. The photo-chemical process (as was evident in the retrospective of exquisite films Phil Solomon presented in subsequent programs at the festival) contains its own inherent magic that somehow continues to fascinate, even as it heads toward extinction. Whether acknowledged by the filmmaker or not, death hovers like specter over the film, not only in the imagery (a photo of a tombstone and other old photographs) and in its obsession with earlier technology (phonograph and cassettes), but even in the lyrics of the Scottish song “The Carpenter and the Sexton,” which we hear on the soundtrack at one point.

Certain shots are remarkably crisp, yet deliberately grainy, which gives Rivers’s film a liveliness lacking in most digital films. Processing blotches from home development swirl about the image, and the light within certain shots pulsates and flickers, giving an energy and sense of materiality to Two Years at Sea. Rivers’s rigorous framing often places the subject at the right hand side of the frame, such as in the scenes of him showering or fishing, or the extended portrait shot of Jake at the film’s end.

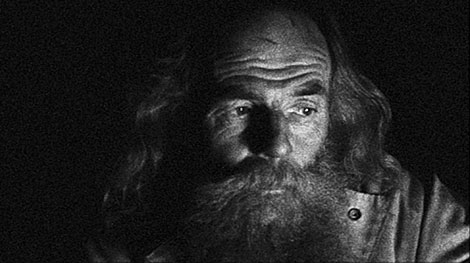

In the final shot, which lasts close to 8 minutes, the camera frames Jake in close-up in front of a cracking fire that illuminates his face. He has a contemplative expression. At one point he rubs his head and rests his head on his hand. His eyes momentarily dart around the frame. He repositions his body and appears to get sleepy as the dying fire’s light ever so slowly begins to fade. This spectacular shot conjures up an antiquated Andy Warhol-like Screen Test, as the image of Jake gradually fades to black and transforms into bouncing grain.

Postscript: The Wisconsin Film Festival was pretty awesome. I saw many great films over the course of 5 days. Ben Sachs of the Chicago Reader provides a very humorous, outsider perspective on the festival.